openspace.sfmoma.org/2016/07/a-conversation-with-mike-kuchar

SFMOMA Open Space, July 19, 2016

A conversation with Mike Kuchar

by Matt Borruso + Gordon Faylor

I first met Mike Kuchar in 2011 when I visited the apartment he had shared with his late twin brother

George. It was a studio visit with my friends Margaret Tedesco and Patrick Jackson. The space was

filled with paintings, books, and photographs — memorabilia from decades of filmmaking. Statuary was

everywhere: lawn ornaments, Greek nudes, and a remarkably buff Yeti. We watched some of Mike’s

early films, and were thrilled to see a stash of his old drawings dating back to the ’80s.

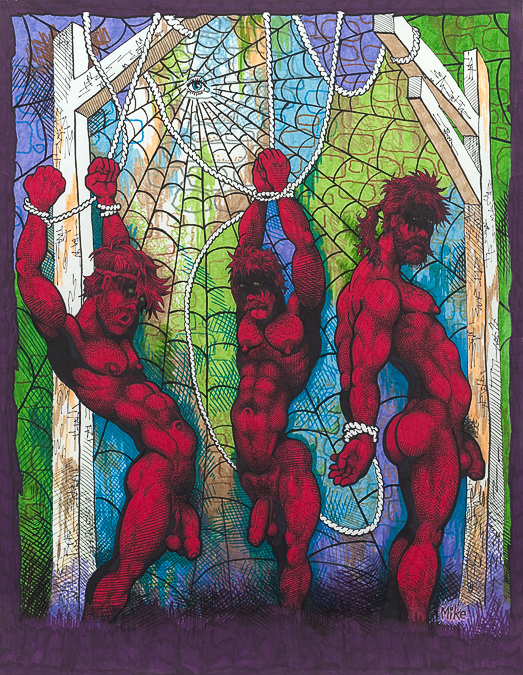

Since then, Mike’s work has had an incredible resurgence. His films have always been at the forefront

of critical reception, but his drawings have also recently received major attention. Originally appearing

in magazines like Gay Heart Throbs, they were first shown in a gallery setting at Tedesco’s 2nd

floor projects in 2008. The drawings have subsequently appeared at Frieze, Kimmerich Galerie in

Berlin, the ICA and Tate in London, Francois Ghebaly in Los Angeles, and elsewhere.

When Gordon Faylor asked me to host a conversation with Mike for Open Space, I welcomed the

opportunity. Mike and I share some similar interests in vintage comics, cavemen, and science fiction,

among others, and I wanted to ask him about his connections to other underground filmmakers,

underground comics, and his working process. We decided to meet at my studio, which, like Mike’s

apartment, is also full of “things”: sculptures, books, figurines, detritus.

Mike Kuchar is a true San Francisco treasure. His uncompromising output spans more than sixty

years, and reminds us of the often forgotten value of individual vision and non-conformity. The few

meetings I have had with Mike always leave me feeling completely inspired, and this time was no

exception. Below are excerpts from that wide ranging two-hour conversation, between Mike, Gordon,

and myself, which took place in my studio on May 18th, 2016.

—Matt Borruso

KUCHAR: I went to public school, and the teachers said I had talent because they liked my

drawings and all. There were two art schools in New York: Music and Art, which was like a fine arts

school, and Industrial Art. They said, “Go to the commercial art school, because fine artists, in the

beginning, always starve.” And you know, they got a point there. And I did get a commercial art job

for a while. I did photo retouching on the big fashion models. It was for all the big agencies, I

would retouch all the big models of the day.

BORRUSO: Were you doing airbrush retouching?

KUCHAR: At that time, it was like eight-by-ten, eleven-by-fourteen transparencies. These were big

slides. And what we did, with translucent dyes, we would retouch those big transparencies over a

light box. If the background was light and the dress was sticking out and it was dark, you had to

bleach and lighten the emulsion. And then it was up to the retoucher to paint back the background

onto that emulsion that was sort of lightened.

It was a meticulous kind of thing. It paid well and all, but I was not really interested. I was

only interested in whatever inspired me. I liked making movies. I would be making 8 mm movies of

my brother and 16 mm movies too. That’s really what I was interested in. And painting every so

often. Sometimes a movie needed a matte painting, and I was able to do it.

BORRUSO: What other commercial work did you do?

KUCHAR: I did a couple of movies for German television. I was the cinematographer for Rosa von

Praunheim. But then the movies I had made with my brother caught on. I didn’t know I was part of

a movement —what became the underground movement.

Cameras became a consumer product. You could buy a movie camera. So it wasn’t only that the major

studios or TV companies were making movies, but now people in the apartments, like artists, who

were, some of them, reputable. I mean, I knew Andy Warhol, I knew a whole bunch of other people who

decided to get to their ideas, their temperament, their kind of approach to the visual stuff using

the camera. Studios used to make stories, movies about crazy people; but now crazy people were

actually making movies, so you’re getting the real thing. [laughter] I mean that in a good way.

That guy Jack Smith. He was, well, a tormented person, you know? But you see his movies, you get

into his mind and fantasies. You know, I could use the word crazy. But remember, isn’t it the Greeks

that said the crazy people are the ones who’re closer to the gods or understand the chaos in

creation or something?

BORRUSO: How did you end up doing underground comics? I’m interested in the connection

between your filmmaking and this two-dimensional work — the drawing work.

KUCHAR: Yes. You know, I remember I was editing something at four in the morning in the apartment.

And through the wall, the person on the other side — I would hear tinkling of a brush in a glass. And I

said, “Somebody else, too — some other soul, too, is up late working.” And she would hear me, with

the splicer, cutting the pictures, and I would hear her. And finally I said, “What are you doing? You’re

working on your painting?” And she was working on her watercolors. But anyway, she also saw my

drawings and she said she knew somebody who was writing for this comic book that was being printed

privately. They needed an illustrator for their latest issues. This guy would publish these comic

books called Gay Heartthrobs. This was back in the early seventies. They needed somebody. I guess

oneof their illustrators dropped out. Well, they weren’t very good.

Also they didn’t know the subject. It’s strange. The man’s idea was good — Larry Fuller — but the

drawings were not good. They really didn’t know the subject. So anyway, she told the fellow who wrote

for the publisher that she knew somebody who might be good for illustrating the stories. And I did a

few samples and they loved it. They loved it. I don’t blame them because what they had before was not

very good. [laughter] They asked me to do three stories and they just gave me complete freedom to

illustrate it the way I thought, because they trusted me. So it went out on the market. And then months

later, I would get telephone calls from — I don’t know how they found my telephone number. I only

printed my first name, Mike, because it’s that kind of work. I considered this my extra sort of career,

my little secret career.

Anyway, I would get the call from these editors who had seen my work for these other magazines,

which dealt with kind of erotic, sexy stuff. And they asked if I could illustrate for them, for their

publication? They would send me a story and they would say, “can you do two or three illustrations

for each?” And they would give me fifty dollars. I was on poverty row, so I said, “oh, well, here I’m

getting fifty dollars for each black and white drawing, and that’s good.” It got me back into drawing.

BORRUSO: George was doing comic books, as well, right? He did the H.P Lovecraft comic for Arcade.

KUCHAR: Yes. Now, this is very, very interesting, considering the underground that’s going on. Okay,

that was going on in New York. But like I say, it was not people that got together and did these movies.

It just was spontaneous. But next door to us in California here actually was the hub of a movement —

individuals were doing comic books. My brother and I were good friends with R. Crumb. There was a

guy that did Zippy the Pinhead, and then there’s Art Spiegelman, who now actually does covers for the

big magazines —

BORRUSO: New Yorker.

KUCHAR: Yeah. You know? I mean, good for him and all. I mean, he was funny. He was kind of an

intellectual type. But next door, which was Bill Griffith’s place, they would get together and have

publishing meetings every month or two. So that was happening right next door to a bungalow we had.

And then in the other bungalow next to us, it was happening there, too. That was Art Spiegelman’s

place.

BORRUSO: What neighborhood was this in?

KUCHAR: This was off of Dolores Street and I think around 18th or 19th, if I remember.

BORRUSO: In the seventies?

KUCHAR: Yeah. And anyway, Art Spiegelman and Crumb loved our 8 mm movies. After the

meetings, he’d come over and we’d play our 8 mm movies for them.

But Art Spiegelman also loved my brother’s drawings, and they had him do a couple comic strips for

this magazine, Arcade. And my brother, I think, was one of the early people to do biographies of

authors. And we were big Lovecraft fans, so he did one of Lovecraft. I didn’t do any work for them.

Mainly, I worked with the bigger publishers that would sell their sexy books on the newsstand. I did

digest-size books for them. But it’s interesting, isn’t it? These two movements. One was a new way of

— or acceptance of movie making, and it was labeled the underground. And then when my brother

moved to California and I followed him, it was this movement that was going on with the illustrations

and comic books. It was underground comics, which opened the door to other explorations of the

psyche and the libido and whatever, which came out in those magazines. It just happened. I didn’t

seek out any of these things.

BORRUSO: But you also both lived in New York and San Francisco… is that right?

KUCHAR: Yeah.

BORRUSO: It seems like underground comics are much more San Francisco, and the initial

underground film scene you were involved in was much more New York.

KUCHAR: Yeah. My brother, he got stationed here because he got a job at the San Francisco Art

Institute. Then I would come out, and I’d go back and forth. And eventually I stayed here.

BORRUSO: What about Crumb? I’m always interested in the connections between artists.

KUCHAR: Well, yes. He was a delightful, delightful man. Delightful. Very unpretentious, very like, real.

Almost like a small town or a country man. He always wore a brown suit. Like a brown suit and a white

shirt. A very, very nice, very down-to-earth person. A little quiet. Yeah.

BORRUSO: So unlike his comic book persona…

KUCHAR: Yeah. [laughter] No. No. With the libido and all that stuff, it really came pouring out. It was

wonderful. Wonderful. No, a very, very charming, slightly-built man, you know.

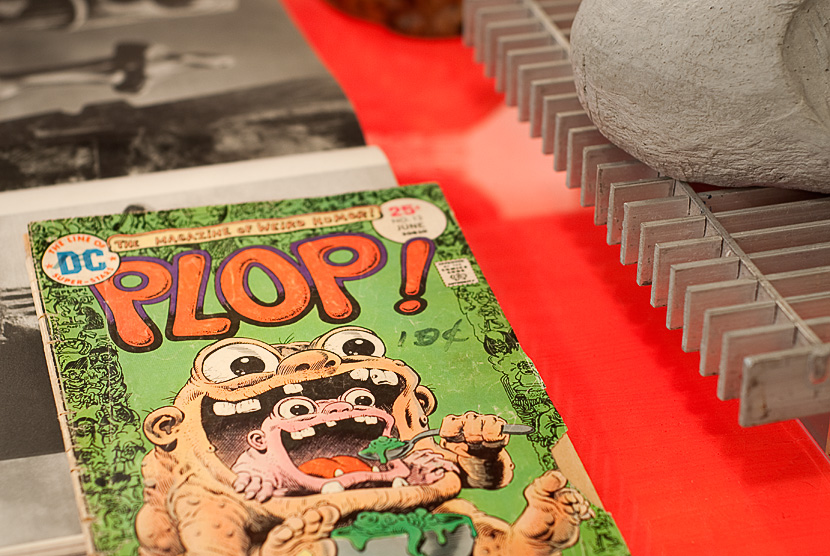

BORRUSO: I know you also like older comics. Last time I was at your apartment I noticed you had an

EC collection on the shelf. And I know you like Wally Wood a lot.

KUCHAR: Oh, yes. Yes. You know, all these people, we open doors for each other. Artists open

doors for each other. We show the possibility, and then that opens doors for other people to explore.

Wally Wood I found very inspiring. You know I would see his drawings. And maybe that, too, was the

impetus for me to draw, because of the effect his drawings had, or the magic and the power. I met

the man.

BORRUSO: Oh, really?

KUCHAR: Yes. And that was a great thrill. A great thrill.

BORRUSO: I really like his drawings, as well. They have a special quality. Could you describe why

you were attracted to them?

KUCHAR: What I liked about Wally Wood, his men were so masculine. And his women were

voluptuous. The space ships were gleaming metal. These elemental things. And the monsters were

absolutely hideous. They were frightening. [laughter] So you got this play of things, you got this

surface — he did amazing things with metallic rocket ships. They really look like metal. I mean, they

had the feel of metal. [Borruso pulls out a copy of PLOP! #13] Oh, yeah, well — well, he did this cover,

didn’the? How do you get that ability to put that aura into a drawing like that, you know? So the males and

females, they were especially powerful for me.

Also I find comic books are really storyboards. And each panel is an angle and it says something. I

mean, you’ve got bubbles coming out of the people’s heads. So it’s a progression; it very much

relates to movies. You’ve got individual shots and angles, and then you’ve got the composition, then

you’ve got the costumes and all of that. All of that’s incorporated.

BORRUSO: Do you storyboard your own films?

KUCHAR: For my own, no. I use instinct.

BORRUSO: Even for the older films, like Sins of the Fleshapoids? It’s just completely improv?

KUCHAR: Yeah. I don’t even know the endings. If I knew the ending, maybe I wouldn’t make the picture.

I have to discover it. I have to see what I’m getting into. I knew I wanted to do a costume picture. I knew

I liked Biblical epics, Hercules movies. And I also like science fiction, so I kind of mixed them all together.

And then as you go into it, it starts to develop. You know, with a lot of pictures, you know what it is?

Sometimes it’s like you’re on a psychiatry couch. You just start talking. It’s going to come out. All of the

subconscious will come out. All you’ve got to do is start talking. Either that or just pick up a camera and

start aiming it — and what you’re aiming at also has influence on how you’re using them or how the

camera is depicting them. And it brings out feelings that you have for your subject, putting them into some

kind of new form that’s emotional, that has its own kind of psychological drive. And as you keep, in this

case, filming — or I guess it’s the same thing with painting — you bring out what’s in the subconscious,

what’s there all the time. Those mediums open up the door for it.

And it could be a canvas or a screen. You begin to see what it is. It becomes clearer. All the motivations,

all the drives. Sometimes with people, you know, there’s a certain way you desire to portray them or

desire to put them in situations. It’s all subconscious, it’s all the libido — it’s all coming out. Then

you see what you got and you see where it’s leading, and then you have to put the final structure to it

and come to a certain conclusion, or to complete it in a way that feels fulfilled, you know? Then the

control starts to come in, because you have to now give it a definite meaning or resolve it.

BORRUSO: So certainly those desires drive your films, but I’m also interested in your film influences.

What mainstream films were you initially inspired by?

KUCHAR: You know, even the stupidest movie or the most despised movie, there’s always something

that is a spark. There’s something that can be explored or affects you in a certain way. I love Hollywood

movies. That’s how I learned movie making — when I was watching the picture, I was also seeing how

they were made, in some ways. And I love junk stuff. I love B-movies, I love the cheap science fiction

movies of the fifties.

I love to look at paintings too, because in some ways, they also help me as a cinematographer. You

see a painting and the colors that are used, the composition — there’s magic in an image. Something

will affect you. There’s magic. There’s a sense of atmosphere, light and mood. I always find the

mediums are all interchangeable.

BORRUSO: I also wanted to know about your collecting — all the stuff that you have in your

apartment. The statuary collection is just amazing.

KUCHAR: Oh, yeah. By the way, I’m going to get a museum-quality Tyrannosaurus rex statue,

another one. [laughter] I don’t know what it is. I used to go to museums and I love those statues

of the dinosaurs.

I like statuary, I like visual stimulation around the house. Sometimes after I’m busy doing something,

I sit in the house, and then I’ve got all these objects around and they kind of hold my attention.

They’re pleasant. I want to create a kind of sanctuary, a kind of museum or a jungle den or a religious

temple. I’d like to be surrounded by that.

BORRUSO: Do you ever buy used things? Do you ever go to the flea market or anything like that?

KUCHAR: My brother, he loved kitsch. Before, the place was all full of that kind of stuff. But what

happened was when he passed away, it was awful, awful. But the house, pretty much, he had

decorated it — it had all this kitsch stuff. And I had to change the look of the place, because I

would expect to find him there, if it was like the way he had always had set it up. I’d come home and

he’s not there; it would only rub it in. Everything — all the photos or books about him and about

authors that signed books to him — it’s all there; but I physically had to change the look of the

place. So I put my interest in this kind of statuary and I gave it a new aura. But my brother’s

spirit is all there.

BORRUSO: Do you use the statuary as a reference for your drawings, as well? When you draw, does it

just come right out of your head, or do you —

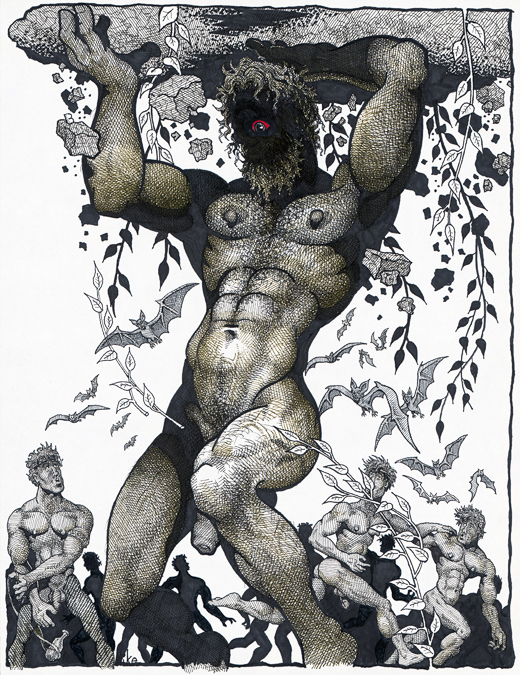

KUCHAR: Yes. You know what I do? I have a flow of action. Lines, a flow of lines. If it’s a figure, it’s

how the figure is to be. Then I try to flesh it out. I have to look in the mirror, I have to check to see if I am

missing something. What‘s missing that would give these cartoons more fleshiness? They’re juicy

cartoons, in a way. So I use myself. I look in the mirror and I say, you know, I should have a vein here

or whatever. Hands are problematic. So I always have to check the character’s hands.

BORRUSO: …I like to have something to draw from, to look at.

KUCHAR: It’s all in one’s approach.

BORRUSO: But I think it’s interesting that you are the model for your drawings.

KUCHAR: Yeah. I mean, I won’t look like those overripe characters I do. I always say: hold back a bit.

It should be more of a tease or something. And you know, I exaggerate. Because why not? I put in

things that I myself don’t see that should be in that style or in that genre of these homoerotic illustrations.

I put in things that I think are important. I mean, like humor, or a mixture of ages. And I play with things,

you know, I try to make them more humorous, witty, and real.

You know, like when you took their clothes off, but didn’t take their tie off or something. [laughter] Or

they have eyeglasses on. I think that’s very charming. It’s real if they have their eyeglasses on. I try to

humanize it, not make it so clone-like. Also, I add a lot of hair on the body because the hair molds the

drawing. [laughter] You know, it puts texture into the drawing.

BORRUSO: I guess now it’s different because you’re making these drawings for gallery shows, and

they were never really made for that reason before. When we went to your house, they were —

KUCHAR: They were in the closet for years.

BORRUSO: When we went, you were like, “Oh, I’ve got these drawings. They’re under a sleeping

bag in the closet.” [laughs]

KUCHAR: They were in the closet for years. Margaret [Tedesco] came over to visit and she saw

one thing hanging on the wall, a sketch. And I said, “I’ve got more I could show.” I was a little shy.

But I showed them to her and she liked them very much. And it was through her that there was a

resurgent interest in my drawings. Doing this type of work, I know it has to be a certain kind of thing.

It has to be geared for the sexy magazines. Yet at the same time, I try to make them good drawings.

BORRUSO: They are good drawings.

KUCHAR: Thank you. I felt that was important. In other words, it should work within what it’s made for;

but also it should work as an interesting composition. You know, it should stand on many legs, be like a

solid table, so it can work.

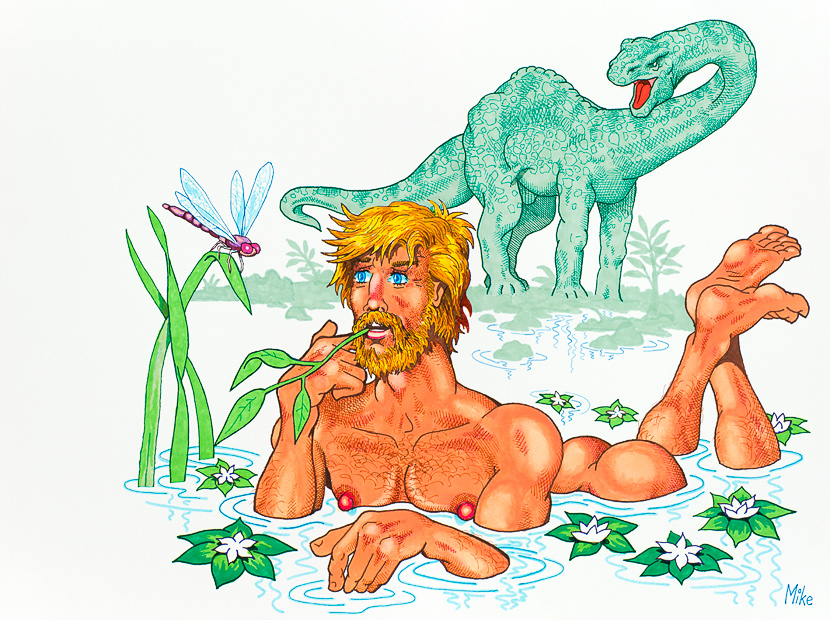

The two pictures that will show at the gallery here, you know, I’m enjoying so much the homoerotic in

them. Because that was my assignment, so I didn’t mind. For years, I would illustrate for magazines

that dealt with that subject and all, and it just becomes natural for me to do that, or automatic.

BORRUSO: So you’re still known purely as Mike for all those drawings?

KUCHAR: Yeah. I still put Mike. [laughter]

BORRUSO: The dinosaurs are very specific to you, though.

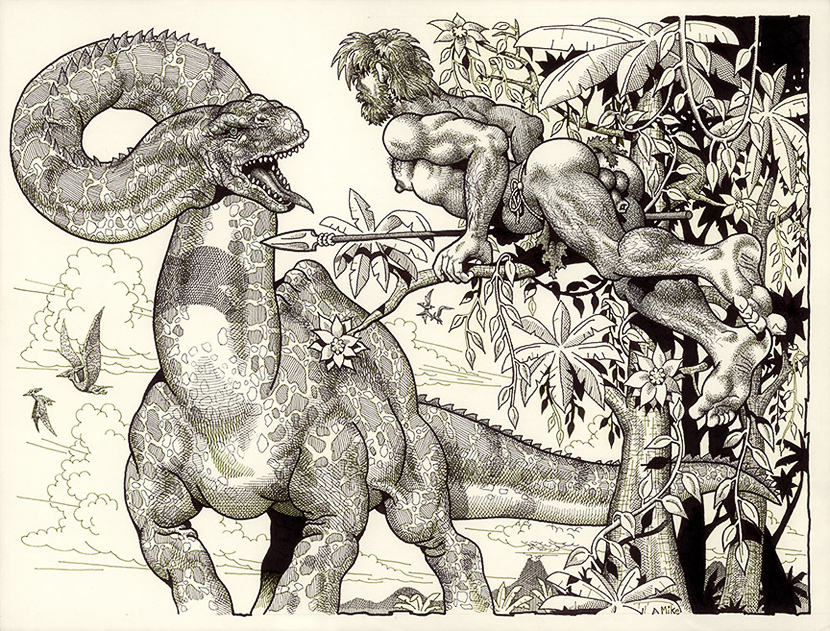

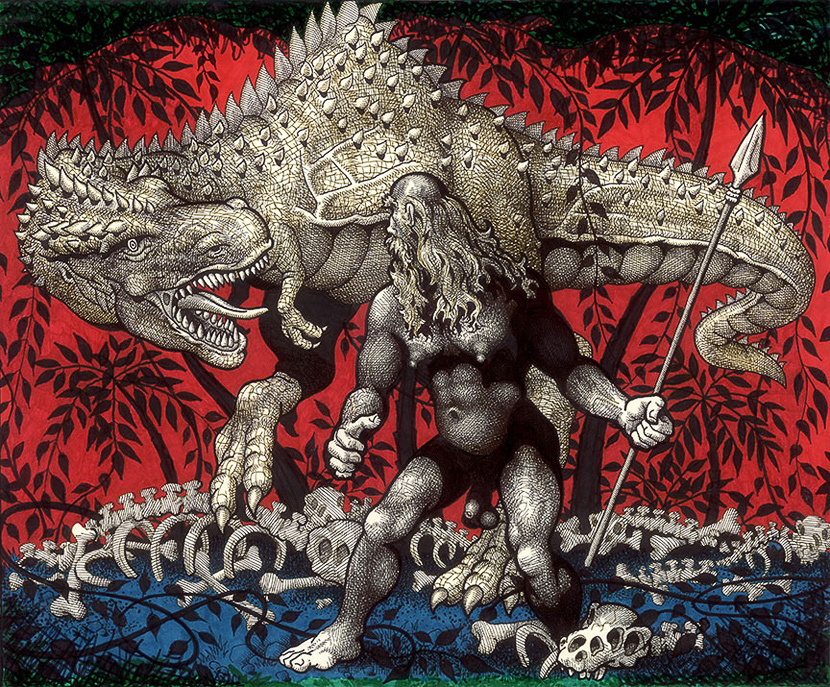

KUCHAR: Oh, yeah. Okay, here’s where the dinosaurs come in. Sometimes in these magazines,

they’d ask me to write stories and all. I’d do cave people stories, cavemen stories. And this was my

chance to put dinosaurs in. I mean, you know, dinosaurs didn’t live with the cavemen, but this is a way

for me to use my fascination with dinosaurs — I always admired the great painters of the Natural History

Museum. Charles R. Knight, you know?

BORRUSO: Yes! I love Charles Knight.

KUCHAR: Oh! Yeah. And I always admired his work. And I wanted to see — try to see if I could draw

good dinosaurs. He was a great inspiration to me, Charles R. Knight.

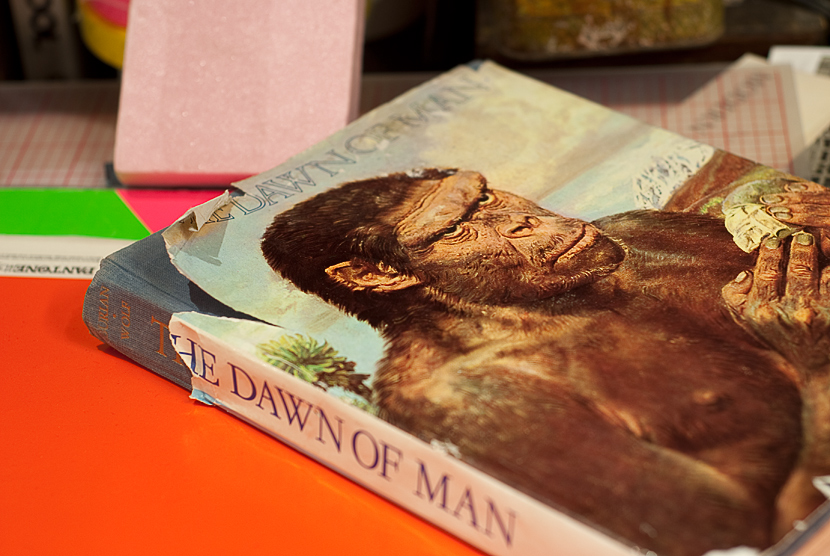

BORRUSO: Yeah. The other artist that I really like is Zdeněk Burian. Do you know him?

KUCHAR: If I saw the work, probably. I can’t put the name —

BORRUSO: His books have been a big inspiration for me. [Matt presents a copy of Josef Wolf

and Zdeněk Burian’s The Dawn of Man]

KUCHAR: Oh, this guy, yes. He’s wonderful, yeah.

BORRUSO: And the new films you’re making, the ones that you showed us last time, they’re a series,

right?

KUCHAR: Yeah, I call them the Soul Searching series. I just finished one a couple days ago. You see

the head, you see the face, [but] they’re doing internal thinking. They’re either trying to confront some

kind of inner turbulence, a doubt, maybe self-doubt. Or they’re trying to figure out their existence or

why they’re existing.

BORRUSO: Do you think it’s changed for you over the years? Would you think right now that you have

different concerns than you did? Your newer pictures seem more self-reflective…

KUCHAR: You do what’s natural to you. This is all self-motivated, for the most part. Except for the

illustrations that I’m asked to do for the magazines. So I can look at my older work and say they are

what they are. They live with whatever vitality they have because it was genuine. I could probably

never do that again. It has to do with the people you knew. As you grow older and older, you think

more. That’s one thing I find. I find that I was more spontaneous — well, I’m still spontaneous. But you

tend to think more as you get older. You can change, but it’s not to eradicate what you’ve done before;

it’s just you follow whatever course comes to you, whatever feels natural. You know? Just whatever is

real to you. Or whatever you are dealing with, you deal with as truthfully as you can, with either the

subject or with yourself, in relating to whatever the subject is.

KUCHAR: So what theme are you working on at the moment?

BORRUSO: I’m making a lot of sculptures these days… from found objects. I look for these very

specific things, and then I put them together sort of like collages. And a lot of the objects are cast. I’ll

remake them… cast them in wax or concrete.

KUCHAR: There’s something very organically captivating about it, you know.

BORRUSO: I’ve also been making a lot of books of collages, found photographs, and digital

manipulations. I’ve been teaching myself how to actually make and bind the books. And a big part of

my work is looking for all this paper and these magazines and the objects that I use. A big part of what

I do is just the looking for things.

KUCHAR: Well, you certainly are putting them to new use. It’s very evocative, very compelling and

like a new entering of a new world.

BORRUSO: Thank you.

KUCHAR: It’s familiar in a new way. But there’s a magic. It’s like a new world, with the world that is

now and with products in it.

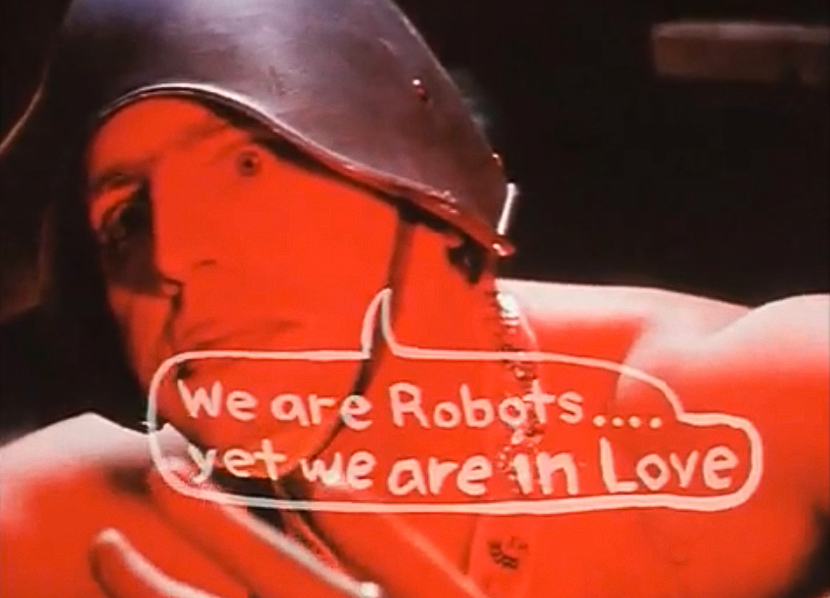

FAYLOR: That’s evident in your work as well. Like in Sins of the Fleshapoids, the characters are

eating Wise potato chips. It’s a new world, but… there’s this resonance of older products that somehow

seeps in.

KUCHAR: Well, you know, movies are phony. Movies are fake. They’re constructions. They’re not real

at all. So I guess I put that in just to jumble things up. Because movies are illusions. I used to go to

movies, and while I’m looking at the big close-ups, I think about the eyelashes, those big eyelashes. It’s

makeup. I mean, it’s beautiful, I love it. But sometimes I overdid it… I overdo it.

And I used to like bad acting. I wouldn’t ridicule it, I’d like it. It shows that the people are brave, when

they get up and they’re trying to participate and whatever, but they fail beautifully or something. Like when

I made my most popular picture, Sins of the Fleshapoids, somehow — I didn’t realize it, but there

was a need then for camp.

Camp, the feeling of camp. What is it? Somebody came up with camp. You know, to me, camp is like you

set up your tent on an established recreation center. You set your tent up on it and then it’s part of the

recreation; you have fun with it. And Sins of the Fleshapoids was like setting up the tent in a

Hollywood genre. The makeup is too much. And when the music comes on, it’s a little too loud. It’s all

obvious. Evident. But it’s more like a send up. Or it’s the beauty of the artificiality of it.

And I used to see, also, those musclemen in the movies. They look great, but they can’t act. And so of

course, the person in mine, he looked okay, but he could not act. He was the worst actor. But there was

this iconic beauty. It’s like this kind of glorious put-on in a costume. What started me with that picture, I

was listening to electronic music and I said, “I want to do science fiction.” That was it. I wanted to do a

science fiction picture.

You know, there’s all kinds of inspiration. It just could start with the most basic, elemental thing or the

simplest thing, and then it begins to escalate into something. That’s always the start of the flame, the fire.