http://blog.sfmoma.org/2012/02/collection-rotation34/

SFMOMA Open Space, February 13, 2012

Collection Rotation: Matt Borruso

The following collection reflects my interest in perception, specifically color, juxtaposition, scale,

composition, and the ability of context to alter the meaning of images. When organizing this work I

tried to choose pieces that I imagine had originally challenged visual conventions through their use of

imagery, process, appropriation, and color. While some images are reproduced singly, others are

reproduced in contrasting pairs and combinations that may suggest an alternative, or “third,”

meaning.

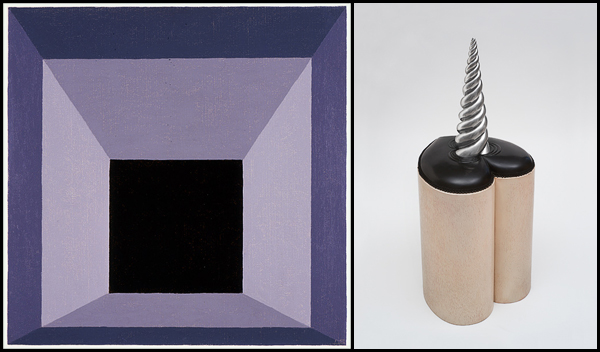

Josef Albers, Homage to the Square: Confident (1954) Albers developed a pragmatic minimalist

process in which oil paint applied straight from the tube onto Masonite was somehow transformed

into magical paintings that seem literally to emit light. Through his teaching, and his book The

Interaction of Color, Albers urges the viewer to see color with new eyes. His simple but painstaking

contrast-and-compare experiments cannot be done digitally, but require real-world materials like paint

and paper. We see what is in front of us — not color as seen from a back-lit computer monitor, but

the actual color and its interactions with light, the time of day, the environment, etc. Albers epitomizes

the idea of physically experiencing the work, of having a bodily reaction to it. When viewing these

paintings we are not passive — we are participants.

But in contrast to this physicality, I also wanted to think about how images are viewed on the screen.

More specifically, I thought a lot about the blog or web format; how we scroll down (rather than

scanning left to right), how the imagery and text on the sidebar affects our visual perception of the

images that we see, how the desktop frames the images, and, further, how we block out the world

around the screen. The blog can be a cluttered space, far removed from the idealized white cube of

the physical realm, but it also allows for differences in representation that can present opportunities

for intentional slippages and alterations of meaning.

For example, we tend to view images more democratically online. 72 dpi web resolution is standard,

the color palette has been minimized for the web, and scale has been rendered nearly irrelevant. It

is difficult to determine scale on a laptop, so everything can become vaguely similar. When a

mural-size painting reduced to an 8” x 6” jpeg is placed next to a 4” x 6” jpeg reproduction of a

playing card, scale can become deceptive. With the blog post, scaling images up or down creates an

overarching equality even more restrictive than physical photographic reproduction due to the

limitations of both the blog template and the screen size.

With this in mind I paired a 2-D painting and a 3-D object, Josef Albers’s Homage to the Square

(1962) alongside the Peter Zecher sculpture Thing 5, Black Heart (1968). Zecher was a sculptor

based in Los Angeles whose work focused on process, materials, and geometry. While disparate,

Albers’s and Zecher’s work can relate to each other via multiple levels of mediation (i.e., the

initial documentary photographs of the works themselves, subsequent digital reproductions of those

photographs, and formatting for the web again via scale, reduced color options, altered context, etc.).

Zecher and Albers are then shown here at equal heights, though Zecher’s sculpture is nearly 4 feet

tall and Albers’ painting is a 2-by-2-foot square. The space in between these images is minimized,

while the black borders frame them to suggest a formal continuity and possible connections in content.

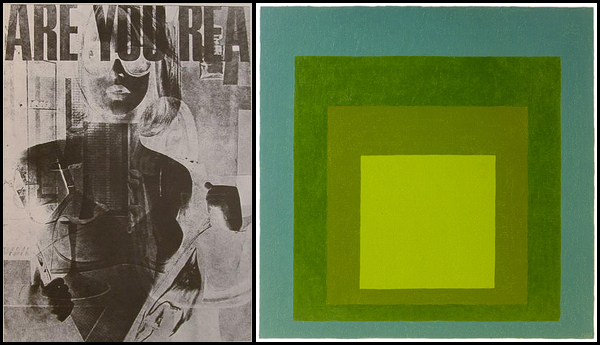

These same framing devices are used to pair an untitled piece from Robert F. Heinecken’s series

Are You Rea (1968) with another Albers Homage to the Square (1969). Heineken, who is having a

resurgence at the moment, was a photographer devoted to working with preexisting photographs. Much

of his work focused on rephotographing magazines, which he often placed over a light table and shot

to expose both sides at once. His work complicates everyday images of commercial advertising,

photojournalism, and pornography through juxtaposition, revealing unexpected connections as we view

both sides simultaneously. Often linked with 1980s appropriationist artists, Heinecken seems

dedicated to undermining the modernist conventions that artists such as Albers pioneered.

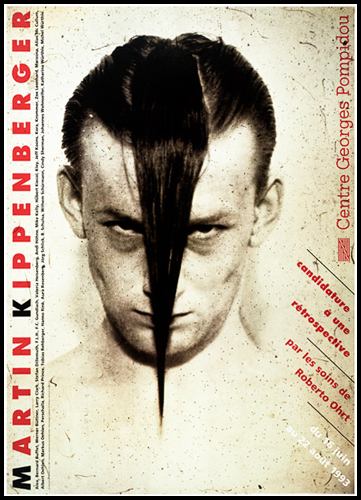

The pre-digital, appropriated, rephotographed, and often degraded image is also ubiquitous to the art

of punk flyers and fanzines of the late seventies and early eighties. The radical degradation and

mutilation of mainstream imagery in early punk graphic design has been so influential on

contemporary visual culture that it’s easy to forget that we haven’t always been looking at things

this way. Heinecken’s work shares an aesthetic connection to this genre — especially with the imagery

of V. Vale’s San Francisco–based Search & Destroy magazine. Since SFMOMA has no copies of

Search and Destroy, nor any punk flyers from this period, I have included Martin Kippenberger’s

poster Candidacy for a Retrospective (1993) with the artist pictured sporting an iconic Misfits

devilock.

These flyers and fanzines are also nothing without collage, a DIY medium with the inherent ability to

make the familiar strange through juxtaposition. For example, in Georges Hugnet’s Initiation

préliminaire aux arcanes de la forêt (First Initiation to the Secrets of the Forest) (1936) the same

figures are merely repeated in multiple positions within a single composition. This work employs the

surrealist cut-and-paste approach to photographs and printed matter that we later see utilized by Jess,

Search & Destroy, Jamie Reid, and the underground graphics of countless anonymous others.

Hugnet’s image evokes Feuillades’s Vampyror Fantomas — a campy Satanic ritual that can be seen

as an early predecessor to the pseudo-evil of Kippenberger’s Misfits tribute. Here Hugnet and Albers’s

Homage to the Square: In May (1960) connect through the democratized yellow web color, but the

dualism between the forbidden unconscious and Albers’s logic remains.

There are also the more straightforward combinations of existing photos in which the mere proximity of

a specific image next to another image can alter the intended meaning of both. Richard Prince’s

Untitled, Three Women with Heads Cast Down (1980) simply uses similar fashion photos to reveal

the ubiquity of certain poses. Identifying these connections is a result of visually scanning image after

image and making connections between them. Prince’s early years working in the tear-sheet

department at Time magazine definitely sharpened his skills in this regard.

In keeping with these ideas of juxtaposition, proximity, and scale I organized a few new examples

utilizing existing photographs taken from the SFMOMA image database. Below is a combination of Bill

Owens’s Tidy Bowl, Walnut Creek (1979) with David Ireland’s Concrete Study(1993).

One thing almost never available to the traditional cut-and-paste collage artist using found print

materials is symmetry. While pretty straightforward in Photoshop, symmetry is impossible with found

photographs unless you re-photograph them and flip them in the darkroom. But the database did reveal

two photographs by Mark Ruwedel, Tonopah and Tidewater #1 (1995) and Southern Pacific #9

(2005), which, though not truly symmetrical, strongly suggest it. These I combined with Martin Parr’s

Untitled [sausage tubes], from the series British Food (1995).

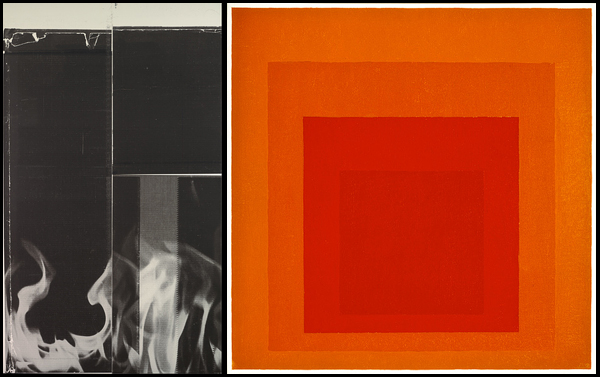

These last images also point directly to the contrast between color and black-and-white that runs

throughout this collection. While Albers turns up the volume on physical experience, the color of Parr’s

sausages or Owens’s bathroom connects us to the full-color world we inhabit. By contrast, many of the

black-and-white or low-key images here utilize or appropriate printed material: black-and-white

photography, or now vintage halftone mass-produced media. These works exploit the abstraction of

black-and-white imagery, which by nature declares itself as a mediated representation.

Below, Albers’s Study for Homage to the Square (1972) sits alongside Untitled (2008) by Wade

Guyton, an artist who often digitally prints over existing images from magazines, books, catalogues,

etc. Guyton coaxes these nonconforming, alien materials into Epson printers to produce paintings that

revel in their drips, stutters, spatters, and overall degradation. This work bypasses photography and

goes straight to the printer, asking us again to reconsider the possibilities of painting through mechanical

means. Here this imperfect, machine-generated work is paired with a last pristine, handmade Albers

square.

As a final example of the shift in vision and seeing that’s taking place through the rise of the digital, the

blog, and screen-based viewing, I chose Tauba Auerbach’s Crumple II (2008), a painting of a

halftone reproduction of a crumpled piece of paper blown up to 80″ x 60″. Like Guyton’s piece, Crumple

II takes some inspiration from the ancient artifacts of print-based media. Reduced here to a small jpeg,

the work looks like a slightly skewed, innocuous, grey rectangle. But in person Crumple II has the

powerful physical effect of total disorientation. While viewing it I was literally unable to focus properly.

Without touching the surface, but only looking at the piece with my eyes, something happened to my

body. If you get a chance, step away from the screen and see this painting — it’s hanging in the

museum right now.