Scanners, Hoarders, and Collectors

http://www.artpractical.com/feature/scanners-hoarders-and-collectors/

Scanners, Hoarders, and Collectors

February 6, 2014

The storage problems facing most families are the result of an increase in the volume of items

to be stored without a proportionate increase in space. As your family grows and interests

expand, so does the demand for storage. But unless you have enlarged your home to keep

pace with your family’s growth, the total storage area has not changed; the units have only

become more crowded.

—Sunset Ideas for Storage in Your Home1Thus there is in the life of a collector a dialectical tension between the poles of

order and disorder.—Walter Benjamin2

Scanners: About

“Scanners is a month-long used bookstore project that highlights the book as a physical object

in an increasingly dematerialized world.”3

Nick Hoff and I wrote this brief sentence in an attempt to succinctly describe the Scanners project, which

would take place during October 2011 at the Mina Dresden Gallery on Valencia Street in San Francisco.

As I recall, it took an extremely long time to write, as we were both trying to define something that had

not yet happened. What follows is an expanded version of that description from my perspective,

incorporating both hindsight and the connections that have emerged between the Scanners project and

my numerous collections.

Scanners: Indeterminate Objects

While the focus at Scanners was set squarely on the physical object, this object was almost always a

book whose nature was bound up in questions of its purpose and/or value. It was a book that was

undecided. This type of book inspired the Scanners project and continues to inspire my personal

collection.

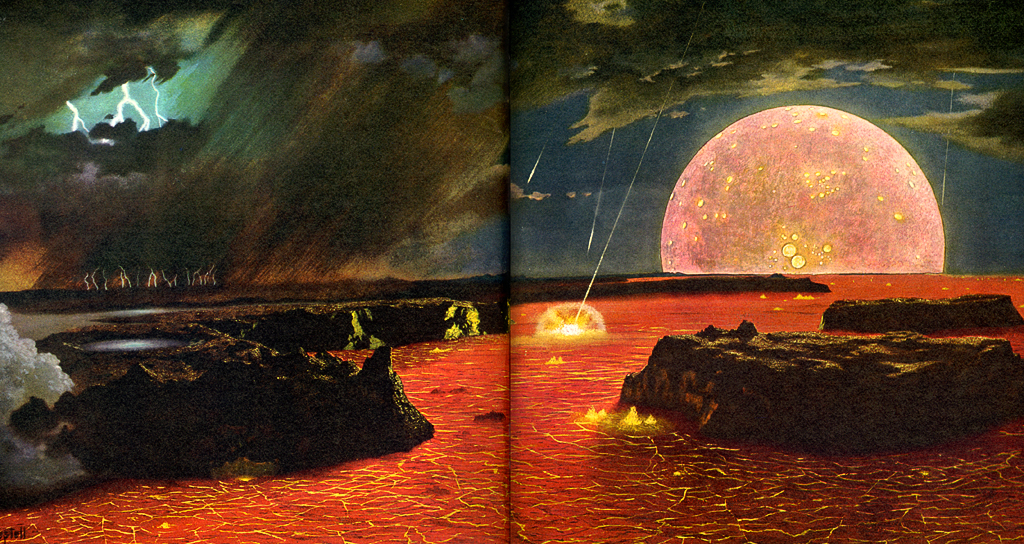

An example of an undecided book might be The World We Live In, Volume 1: The First Four Billion Years

(1962). It’s a Time-Life publication with an evocative cover illustration by Chesley Bonestell, which

transports the viewer to a mid-twentieth-century imagining of a primeval Earth. The book does not supply

current information, it has no monetary value, and it’s far from rare (you can find a copy anywhere). But

it’s an object in which the lack of those qualities in no way diminishes its value as source material and

inspiration—qualities not rationalized by the market.

Scanners: Economic Models

Scanners grew out of the experiences Nick and I had in the used book business. Over the years, I have

bought and sold used and rare books and records regularly at flea markets in London, New York, and

San Francisco in support of my work as an artist. Likewise, Nick supports the work he does as a writer

and translator with his used book business. As a consequence of this part-time self-employment I have

built an extensive visual library that has become fully integrated into my studio projects.

The economics of the used book business was one of the many factors that led to the Scanners project.

When I first began selling books, they went straight to used bookstores or directly to customers at the

flea market. In the late 1990s, online bookselling on websites like Amazon, BookFinder, and AddALL

was in its infancy. Consequently, there was no definitive Internet database for establishing an

agreed-upon value or price for a title. Instead, this calculation was made using an informal knowledge

base developed by booksellers, collectors, and book scouts. The price of a book was determined through

experience, word of mouth, and, most importantly, through an interaction with the book itself. It was a

knowledge gained through the direct handling of a physical object.

With the rise of the Internet marketplace, Nick and I eventually built substantial book inventories online. In

addition, we’ve maintained a stall at the Alemany Flea Market in San Francisco for nearly fifteen years.

But Amazon changed what and how we sold. Books that had a substantial economic value no longer went

to bookstores or the flea market but instead were listed online. And yet it was the books that remained in

our possession—these indeterminate books that were deemed to have no value on Amazon (and often by

the bookstores)—that were frequently the most interesting.

Scanners: Valuation

In a short time, our knowledge, research, and training in recognizing the value of a good or interesting

book had been supplanted by an algorithm created by Amazon. This algorithm dispensed with taste and

knowledge in favor of the lowest price and/or highest sales ranking. We knew that not all books could or

should be sorted this way, and we had years of experience in determining value by our own standards.

Suddenly, this approach was gone. With Scanners, we wanted to question this Internet database of

books as a small and artificially constructed space defined by money and popularity rather than

aesthetics or information. It was by no means the only space. We wanted to propose that determining

value could be based on something other than the lowest price.

As the outlet for books migrated from a physical space to a virtual space, methods of searching for books

also changed. This search, initially based on visual training and memory, gave way to a search based on

algorithms and databases and the increasing use of specific tools dependent on these databases. Enter

the term scanners, which refers both to a small USB device used to read a book’s bar code and to the

individual operating the device. The scanning tool is most often handheldbut can also be strapped to the

arm and operated by an index finger, melding human and machine. The resultant cyborgs flip through

books and bar codes like treasure hunters with metal detectors on a beach.

But we can see the problem here: bar codes only began to appear on books in the late 1970s. Does this

mean that books without a bar code have no value? To the scanner, both human and machine, they do not.

Scanners: Categories

“Sections in the store were left unmarked and organized according to their own internal logic,

leaving customers to discover patterns on their own. For example, philosophy and critical theory

were not alphabetized but followed paths of influence, while a Havelock-inspired “technologies of

the word” section spanned Homer, the invention of writing, Plato, oral culture, McLuhan, and

typography. The sections themselves were also arranged in a way that invited interpretation. One

run of sections, for instance, began with technologies of the word and ran through poetry,

philosophy, and literature.”—Nick Hoff4

Nick’s comments point to our different approaches when considering organizational strategies for Scanners.

While we both contributed to all sections of the store, Nick’s sections were more concerned with text while

mine were more concerned with images. Inverting the left brain/right brain duality, the store was organized

with visual materials on the left side and text primarily on the right. My sections were purposely left

unorganized. The section on art housed everything from Basil Wolverton and Sophie Calle to Isamu

Noguchi and popsicle-stick sculpture. I wanted to introduce the element of chance to the visual sections. I

wanted visitors to get in there and really look, and I was interested in the inadvertent juxtapositions that

might be uncovered as a result.

Collecting, Culling, Constructing

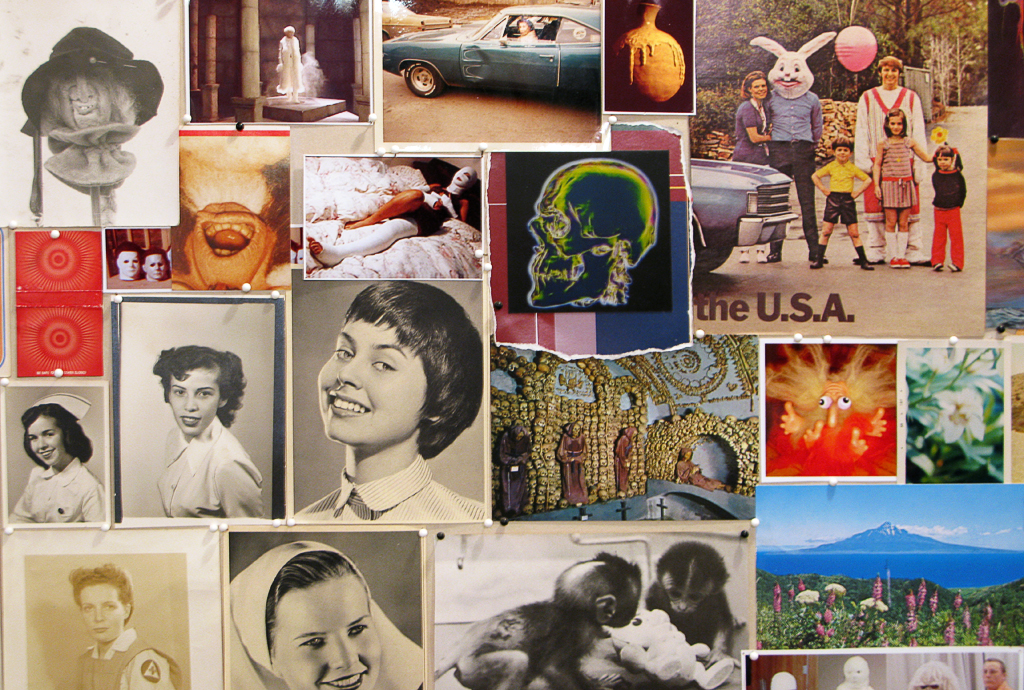

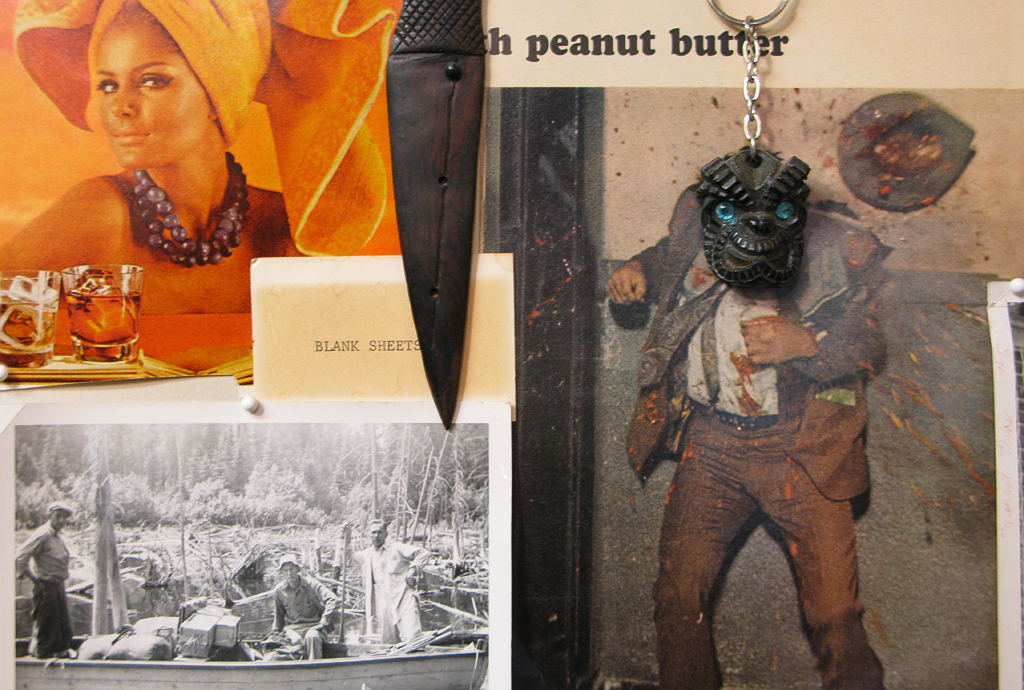

The element of looking is essential to my studio practice and has its roots in the scavenging or salvaging

that I’ve always done in my work with books and ephemera. My project is centered on the collection and

research of visual materials, and it evolves through a methodology that often uses collage as both

investigation and final work. My home studio houses my collections of books and objects, and through

them I construct a world, an alternate universe. This accumulation provides the space I most want to

inhabit. It’s a collection of old and new things: books, artwork, trolls, color wheels, photo collections,

paper and ephemera, latex monster masks and props, ceramic mushrooms, holograms, underground

comix, images of cavemen, and old wood paneling, among other things. Outside, succulents grow from

cuttings and abandoned plants. It is a collection of things that are dead and alive. Collecting these

objects saves them and gives them life. Some of them are reconfigured into new things and new pieces.

Others just lay there, waiting.

My collections are an integral part of who I am. On one hand, these piles of materials are a requirement

for my work, as well as a comfort. The floor space, walls, and tabletops of my studio have been

completely given over to my collections for many years. On the other hand, these piles threaten the order

of my existence.

In 2012, I realized that I physically could not see my work through the clutter and spent six months

cleaning and emptying half of the studio. When I was finished, the space was split in two: one side to

look at things and the other side to work on things. This design strategy also applies to my book

collection and my relationship to objects in general. There is a constant tension between finding things

and ordering things, between wanting to acquire things and wanting to get rid of things. When I make

work now, I move a few objects from one side of the studio and place them in the other side of the

studio, where I try to see them in a new context—or, maybe more accurately, where I can look at them

out of context. Context can be everything.

Fantasy of Modernist Order

While I can embrace the disorder of my collection, I also find myself seduced by the consumer-grade

modernism that everyone buys into, from the white cube gallery space to IKEA. This is the

contradiction: my constant desire to accumulate and amass is opposed in equal force by my desire to

liquidate and de-access. I imagine living in a geometrically perfect empty space, with my collections

offsite. They would be stored in an immaculate temperature-controlled warehouse equipped with every

sort of fetishistic storage and organizational option available: flat files for my decaying psychedelic

posters and Xeroxed punk rock flyers; archival storage bins for my moldy, rotten magazine collections;

rows of shelving and glassine cover protection for my books; and everything catalogued in a searchable

private database. Rows of tables, where I could examine the objects in my collections under perfect

lighting, would line the center of the room.

This fantasy of order, this fantasy of being able to see everything that has been collected, was briefly

realized with Scanners. The collections, which began as piles of boxes heaped up in basements and

hallways, became exhibits and display pieces. For a single month, we could see what we had been

doing while rummaging through flea markets, garages, and dumpsters for a year. Scanners was held in

a gallery space with white walls and dedicated lighting, a place where “things” were seen out of their

usual context and “value” was created through an isolation of the indeterminate object. In relation to

the flea market, Scanners occupied a space at the opposite end of the spectrum. The gallery setting

brought with it a different set of rules for determining value and a different set of expectations for the

viewer. On many occasions visitors were confused, unsure whether they were encountering an

exhibition or a store. This reaction was something we had not expected but of course welcomed.

Scanners: Building the Collection

For any book collector, finding a special book is a pleasure on par with owning that book. The

memories this creates are integral to the process. With Scanners, collecting was ramped up as Nick

and I spent three to four days a week, sometimes more, for a year buying books specifically for the

project (and this was separate from our primary work in the studio, teaching, writing, and bookselling).

We collected approximately four hundred boxes of books for a store that was open for just one month.

When asked if we’re planning another version of Scanners, I always try to explain the distinction

between pleasurable collecting and the anxiety of mass accumulation.

Completists

My personal collection of books (which grows weekly) is an ambiguous and uncontrolled project. This

ambiguity is why I’ve never considered myself a true collector. In my mind, the true collector is someone

who must have certain objects, acquire complete sets, organize, and have one of everything. The

Internet promises the possibility of this completist viewpoint. It provides the capacity to obsessively

collect, document, and categorize in ways never before possible. From the Google Books Library Project

to the IMDb, there is a current belief in the possibility of actually completing every set, capturing every

loose book, uncovering every film—an idea that if it’s not searchable online then it doesn’t exist. One of

the intentions of Scanners was to question this belief and to suggest the limitations of these structures.

Scanners: Display and Duration

With Scanners, we wanted to highlight the books’ qualities through the use of display. We have always

sold our books in flea market parking lots, where display options consist of moldering card tables and file

boxes on the ground. There, it is understood that you might have to get on your hands and knees to find

the good stuff.

We came indoors to the gallery space with Scanners, and the display strategies of the flea market spread

out. While some of the store was arranged in a conventional fashion (books on shelves, spines out), at

least seventy percent of Scanners was devoted to face-out display. It was important that visitors could

clearly see the covers of the books. From our experience at the flea market, we knew that people were

interested in the books we had laid flat on the tables simply because they were more visible.

At Scanners, we built two sixteen-by-ten-foot tables—three hundred twenty square feet of table space for

face-up display—and then dedicated the entire front half of the gallery to face-out wall display. Some of

the books were permanently affixed to the wall, following the pattern of the source material arranged in

my studio, while a rotating selection of books sat face-out on purpose-built rails. A typical retail store,

where economic factors drive display tactics, might have difficulty surviving with the low

volume-to-square-footage ratio we had at Scanners.

We also liked the idea of a limited duration for this project. One of our ideas for what a bookstore could

be was unintentionally transposed onto the duration of a typical gallery show, and so the store was open

for a month, no longer. The idea that Scanners would be permanent was never our intention. We wanted

this to be an alternative to the typical bookstores that we knew.

Scanners: San Francisco, 2011 and 2014

If we did want to open another Scanners—even for a single month—the climate in San Francisco has

changed so drastically since 2011 that it might not be possible. Certainly, we must have been two of the

last tenants to rent an affordable space on Valencia Street before the current real estate boom. The Mina

Dresden Gallery closed a few months after our project ended, and we were subsequently inundated with

emails inquiring about the availability of the space.

Since the completion of Scanners, Nick and I have continued our book businesses online while our

presence at the Alemany Flea Market has become more infrequent. Part of this is due to the physical

labor involved in the flea market project, but it also reflects a larger change. I started out buying and

selling books in purely physical spaces that were specific to small, local economies, such as the

Chelsea Flea Market in New York or the Alemany Flea Market in San Francisco. In these spaces, the

books that were bought and sold circulated primarily within the local communities.

With the rise of the Internet marketplace, our interaction with local communities of readers and artists

has diminished greatly. The majority of our books are now sold to people outside of San Francisco,

paralleling the reported exodus of local literary and artistic culture from the city. San Francisco is no

longer the used book Mecca it once was, and rising real estate costs have made projects like Scanners

prohibitive. Nick and I continue with our scavenging work in a climate of market rationalization of

objects, and we continue to find amazing things. There may come a point, though, when everything has

been found and catalogued…and there is nothing left of the physical world but the scans.

Notes:

1.Editorial staff of Sunset Books, Sunset Ideas for Storage in Your Home (Menlo Park: Lane Book

Company, 1958), 4.

2. Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library: A Talk About Book Collecting,” in Illuminations: Essays

and Reflections (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 60.

3. “About Scanners,” Scanners, accessed January 3, 2014, http://www.scannersproject.com/about.html.

4. Email exchange with the author, November 24, 2013.

5. All photos: Matt Borruso.